Grades of Stainless Steel: Types, Properties, and Applications

Stainless steel is a versatile and corrosion-resistant alloy composed primarily of iron, chromium, and other elements such as nickel, molybdenum, and carbon. Its unique properties make it indispensable across various industries, including construction, automotive, medical, and kitchenware. The specific grades of stainless steel determine their mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and suitability for particular applications.

Stainless steel, a family of iron-based alloys, is distinguished by its resistance to corrosion. This resistance stems from the formation of a stable passive layer, which shields the underlying metal from the effects of air and moisture, unlike other ferrous alloys.. This rust resistance makes it a preferred material for many applications, including outdoor structures, aqueous environments, food service, and high-temperature uses.

How Is Stainless Steel Made?

Stainless steel can be cast or wrought, with the key difference being how it is formed into the final product.

- Cast stainless steel is produced by pouring liquid metal into a mold to create a specific shape.

- Wrought stainless steel starts at a steel mill, where it is processed into ingots, blooms, billets, or slabs before being shaped further through rolling or hammering.

Wrought stainless steel products are far more common than cast stainless steel products because of their superior strength, versatility, and wide range of applications.

Production Steps of Stainless Steel

- Raw Material Selection

- Stainless steel is made from iron, carbon, and chromium (minimum 10.5%) along with other alloying elements like nickel, molybdenum, and manganese.

- Melting and Alloying

- The raw materials are melted in an electric arc furnace (EAF) at high temperatures (over 1600°C).

- Elements like nickel and molybdenum are added for enhanced corrosion resistance and strength.

- Casting into Forms

- The molten stainless steel is cast into semi-finished forms:

- Ingots (for forging and machining)

- Billets (for long products like bars and rods)

- Slabs (for flat products like sheets and plates)

- The molten stainless steel is cast into semi-finished forms:

- Hot Rolling and Cold Rolling

- The cast stainless steel is then shaped through hot rolling (above recrystallization temperature) or cold rolling (for smoother finishes and greater strength).

- Heat Treatment (Annealing)

- Annealing improves ductility and corrosion resistance by softening the material and removing internal stresses.

- Descaling & Pickling

- After rolling, stainless steel undergoes pickling, where an acid bath removes oxide scales that form during heat treatment.

- Finishing & Fabrication

- Final processes include polishing, grinding, or coating to enhance corrosion resistance and aesthetics.

2. What Is Stainless Steel Made Of?

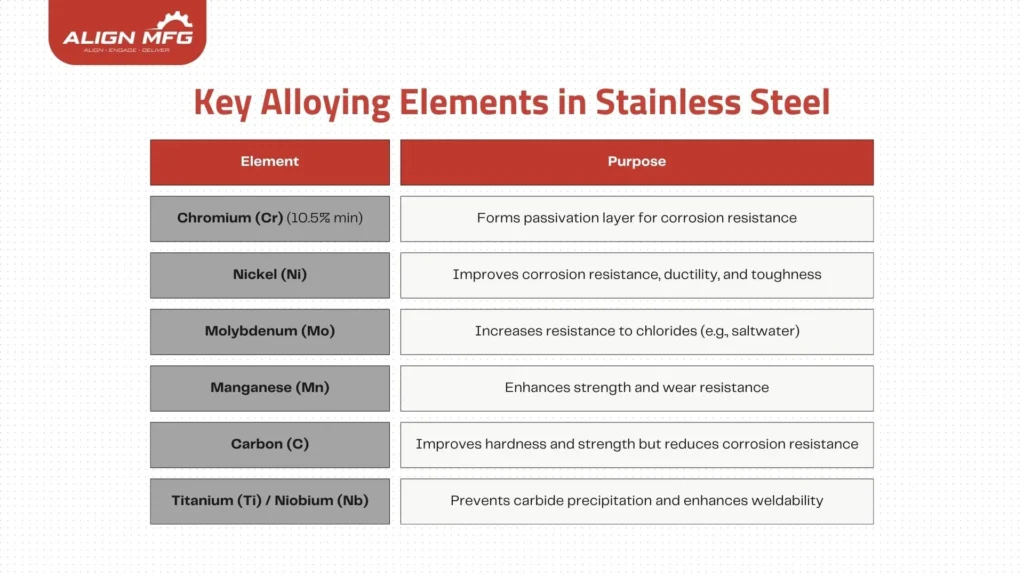

Like all steel, stainless steel starts with iron and carbon. However, its key differentiator is the addition of chromium (Cr), which provides its corrosion resistance.

When stainless steel is exposed to oxygen, the chromium reacts to form a thin passivation layer of chromium (III) oxide (Cr₂O₃). This layer:

- Prevents oxidation (rust)

- Self-heals when scratched, unlike plated metals (e.g., zinc-plated steel, which loses its protection if scratched)

Download our guide to understand the different grades of stainless steel.

Understanding the Microstructures and Technical Aspects of Stainless Steel

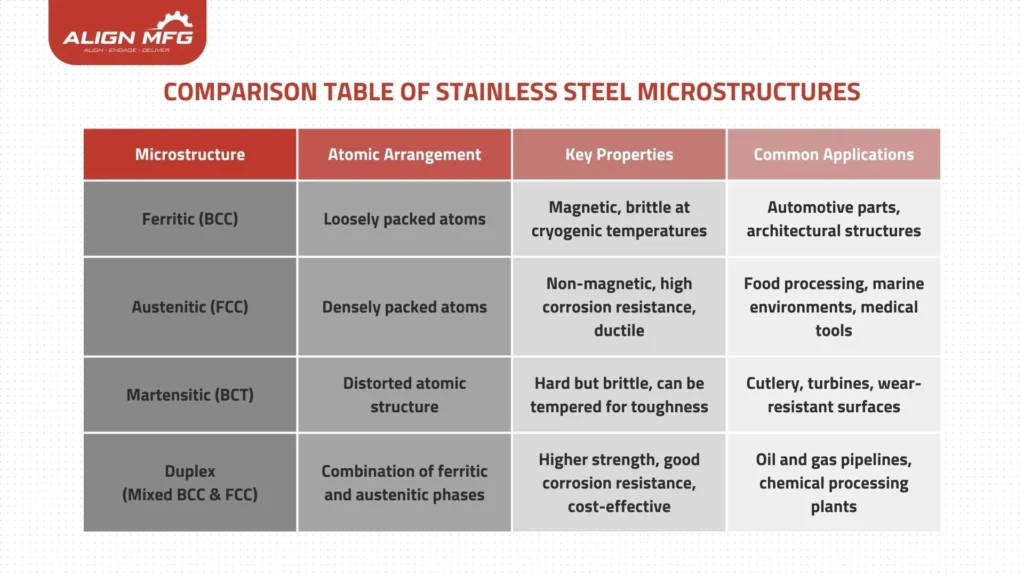

When stainless steel solidifies from its molten state, it forms distinct microstructures that dictate its mechanical properties. The interplay of temperature, elemental composition, and cooling rate influences the crystalline lattice within the steel, leading to variations in strength, ductility, and magnetism.

Microstructural Evolution in Stainless Steel

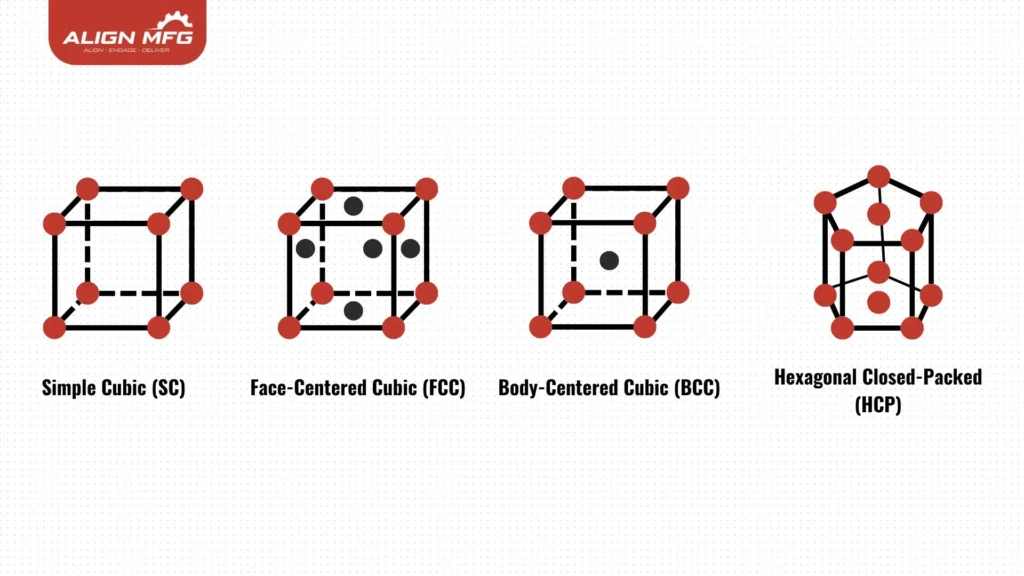

The foundation of stainless steel’s structure lies in the way iron atoms arrange themselves at different temperatures. Three primary phases characterize its transformation:

- Ferrite (α-iron): A body-centered cubic (BCC) structure dominant below 912°C, known for its magnetism and lower ductility.

- Austenite (γ-iron): A face-centered cubic (FCC) structure forming between 912°C and 1394°C, which enhances ductility and corrosion resistance.

- Delta Ferrite (δ-iron): A high-temperature BCC phase appearing above 1395°C before iron fully melts at 1538°C.

Influence of Alloying Elements

The addition of elements such as carbon, nickel, and manganese plays a crucial role in stabilizing these phases. Carbon increases hardness by promoting carbide formation, while nickel enhances the retention of the FCC structure at room temperature. This ability to maintain austenite at ambient conditions is critical for producing austenitic stainless steels, which are highly resistant to corrosion and non-magnetic.

The Role of Cooling and Heat Treatment

Steel’s final properties depend on how it cools post-processing:

- Slow Cooling (Annealing): Allows atoms to arrange into stable configurations, promoting ductility and toughness.

- Rapid Quenching: Traps the lattice in a strained configuration, leading to hard but brittle martensitic structures.

- Tempering: A controlled reheating process that refines martensitic steel, reducing brittleness while maintaining hardness.

Real-World Applications of Stainless Steel Microstructures

- Cryogenic Storage (Austenitic Steel – FCC): Retains strength and ductility even at extremely low temperatures, making it ideal for LNG storage tanks.

- High-Speed Machinery (Martensitic Steel – BCT): Hard, wear-resistant surfaces enable turbine blades and surgical tools to maintain sharpness.

- Bridges and Marine Environments (Duplex Steel – Mixed FCC & BCC): Provides a balance of corrosion resistance and structural strength.

- Magnetic Applications (Ferritic Steel – BCC): Used in motor components and electrical transformers where magnetism is required.

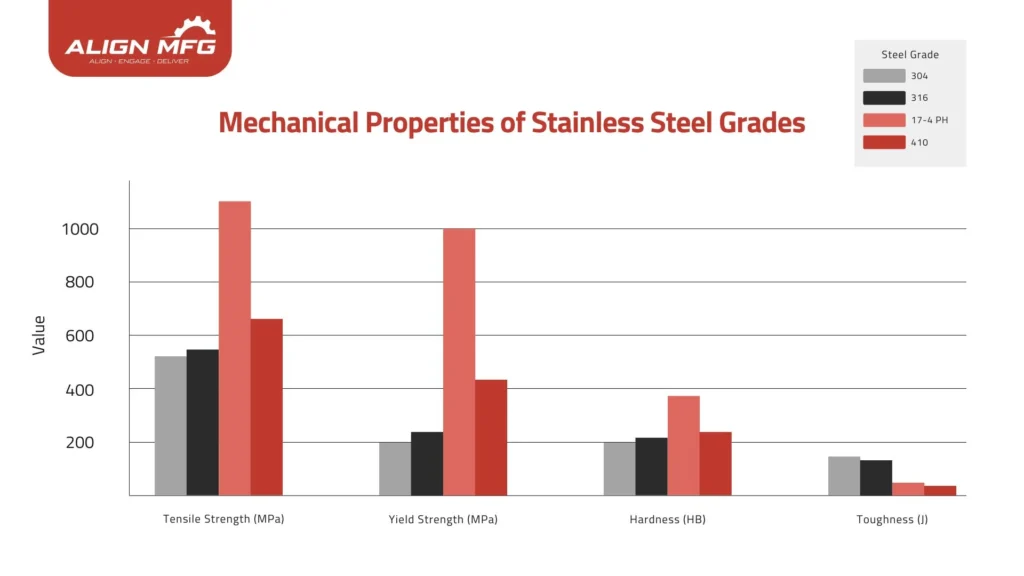

Other Key Factors in Selecting Stainless Steel Grades

When choosing the right stainless steel grade, consider:

- Corrosion Resistance – For marine or chemical environments, 316 or duplex stainless steel is recommended.

- Strength & Hardness – Applications requiring high strength should use martensitic or PH grades.

- Temperature Resistance – 321 and 430 are suitable for high-temperature environments.

- Cost Considerations – 201 or 430 are budget-friendly alternatives for non-critical applications.

- Magnetism – Austenitic stainless steels (300 series) are generally non-magnetic, whereas ferritic and martensitic steels (400 series) are magnetic.

Stainless steel grades vary significantly based on composition, mechanical properties, and applications. 304 and 316 are the most commonly used grades due to their excellent corrosion resistance, while martensitic and duplex grades are preferred for strength and durability.

Understanding the characteristics of each stainless steel grade is crucial for selecting the right material for a specific application. Whether you need stainless steel for kitchenware, medical devices, industrial machinery, or marine environments, choosing the right grade ensures optimal performance and longevity.

For more on stainless steel, request a custom quote or project with Align Manufacturing. We have served the metal manufacturing industry for over a decade and offer a comprehensive range of stainless steel products and services such as sand casting,