Posts by Align Manufacturing

Tempering vs Hardening: What’s the Difference in Steel Treatment?

Steel is one of the most versatile materials used across various industries, from construction to automotive manufacturing. Its unique physical properties can be significantly altered through various treatment processes, primarily hardening and tempering. Understanding these two treatments is crucial for selecting the right material for specific applications.

In this article, we will explore what hardening and tempering entail, their differences, the processes involved, and their impact on the properties of steel.

Understanding Steel Treatment

Before delving into the specifics of hardening and tempering, let’s first understand why steel treatment is necessary. Steel is an alloy primarily made up of iron and carbon, and its mechanical properties can be enhanced through controlled heat treatment processes. These processes can improve hardness, tensile strength, ductility, and toughness.

Hardening

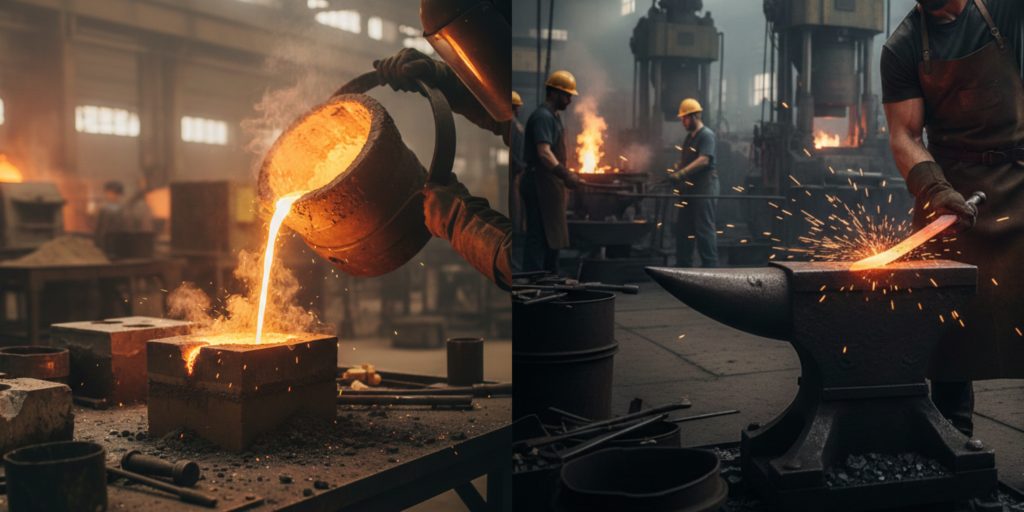

Hardening is a heat treatment process that increases the hardness of steel. It generally involves the following steps:

- Heating: The steel is heated to a specific temperature, usually above its critical temperature, where it transforms from a ferritic (soft) phase to austenitic (hard) phase. This temperature can vary depending on the alloying elements present in the steel.

- Quenching: Once the steel reaches the desired temperature, it is rapidly cooled or “quenched” using water, oil, or air. This rapid cooling transforms the austenite into martensite, a much harder phase of steel.

- Resulting Properties: The resulting steel is hard and wear-resistant, making it suitable for applications requiring high durability, such as cutting tools, gears, and springs.

Advantages of Hardening

- Increased hardness and strength

- Enhanced wear resistance

- Improved tensile strength

Disadvantages of Hardening

- Reduced ductility (the ability to deform without breaking)

- Increased brittleness, which can lead to failure under impact or stress

Tempering

Tempering is a subsequent heat treatment process often performed after hardening. The main goal of tempering is to reduce the brittleness of hardened steel while maintaining most of its hardness. The tempering process encompasses the following steps:

- Heating: The hardened steel is reheated to a lower temperature, typically between 150°C and 700°C (302°F to 1292°F), depending on the desired properties.

- Soaking: The steel is held at this temperature for a specified period, allowing for some of the internal stresses to relieve and the martensite phase to transform into tempered martensite.

- Cooling: After the soaking period, the steel is cooled, usually at room temperature.

Resulting Properties

Through tempering, the steel retains significant hardness but gains improved toughness, ductility, and resilience. This balance makes tempered steel suitable for a wider range of applications, especially where impact resistance is critical.

Advantages of Tempering

- Improved ductility and toughness

- Reduced internal stress

- Better resistance to cracking and failure

Disadvantages of Tempering

- A slight reduction in hardness compared to fully hardened steel

- Requires additional processing time and energy

Key Differences Between Hardening and Tempering

| Aspect | Hardening | Tempering |

| Purpose | Increase hardness and strength | Reduce brittleness and improve toughness |

| Process | Heating followed by rapid quenching | Reheating the hardened steel to a lower temperature |

| Result | Hard, brittle steel | Hard steel with improved ductility and toughness |

| Temperature Range | Above critical temperature | Below critical temperature |

| Sequence | Typically the first step | Usually follows hardening |

| Applications | Cutting tools, dies, and structural components | Springs, gears, and applications requiring more flexibility |

Applications in Industry

Both hardening and tempering play crucial roles across several industries. Here are a few examples where each process is predominantly used:

Applications of Hardened Steel:

- Cutting Tools: Drill bits, saw blades, and tool edges require extreme hardness to withstand wear.

- Construction: Reinforced structures often use hardened steel to ensure durability under heavy loads

- Automotive Industry: Components like crankshafts and gears must endure high stress and fatigue.

Applications of Tempered Steel:

- Structural Components: Beams, plates, and frames that require a combination of strength and ductility to withstand various forces.

- Automotive Springs: Car suspensions require materials that can endure repeated stress without failing.

- Industrial Machinery: Components that must endure both torque and impact, like axles and levers.

Conclusion

Understanding the differences between tempering and hardening is crucial for anyone involved in metalworking. While hardening increases hardness and wear resistance, tempering reduces brittleness and enhances toughness. Properly applying these processes ensures that steel meets specific performance requirements, making it durable in challenging environments.

In countries like Thailand, where metal fabrication is expanding, effective hardening and tempering processes in metal fabrication Thailand are essential for producing high-quality, resilient products that align with global standards. Mastering these techniques will enhance competitiveness and drive advancements in the industry.

What is Ductile Iron? Properties, Strengths, and Industrial Uses

Ductile iron, also known as nodular iron or spheroidal graphite iron, is a type of cast iron known for its high strength, toughness, and durability. It combines the castability and cost advantages of traditional cast iron with mechanical properties closer to steel, making it a popular material across many industries.

This article explains what ductile iron is, its key properties and strengths, and where it is commonly used.

What Is Ductile Iron?

Ductile iron is a cast iron alloy in which the graphite forms as small, rounded nodules rather than flakes. This structure is achieved by adding small amounts of magnesium or cerium to molten iron during production.

In traditional gray cast iron, graphite appears as sharp flakes that create weak points and make the material brittle. In ductile iron, the spherical graphite nodules reduce stress concentration and allow the metal to bend or deform without cracking. This microstructure gives ductile iron its defining characteristic: high ductility combined with excellent strength.

Composition and Production

Ductile iron is primarily made from pig iron, along with several alloying elements such as carbon (3.0% to 4.0%), silicon (2.0% to 3.0%), and small amounts of manganese, phosphorus, and sulfur. The production process involves:

- Melting of Iron: Raw materials are melted in a furnace.

- Inoculation: Magnesium is added to the molten iron to promote the formation of spheroidal graphite.

- Casting: The molten iron is poured into molds to create the desired shapes.

- Cooling: The cast components are cooled slowly to develop the properties of ductile iron.

Key Properties of Ductile Iron

1. High Strength and Toughness

Ductile iron has much higher tensile and yield strength than gray cast iron. Depending on the grade, its tensile strength typically ranges from about 400 to over 900 MPa. It can also absorb significant impact energy, making it resistant to shock and fatigue.

2. Excellent Ductility

As the name suggests, ductile iron can stretch and deform before breaking. Elongation values commonly range from 2% to over 18%, depending on grade and heat treatment. This ductility helps components withstand dynamic loads and sudden stresses.

3. Good Wear and Fatigue Resistance

The nodular graphite structure improves fatigue life and wear resistance. Ductile iron performs well in applications involving repeated loading, vibration, or friction.

4. Good Machinability

Despite its strength, ductile iron is relatively easy to machine compared to steel. The graphite nodules act as chip breakers and provide a degree of self-lubrication, reducing tool wear and machining time.

5. Corrosion Resistance

Ductile iron offers moderate corrosion resistance, especially when combined with protective coatings, linings, or alloying elements. For applications like pipelines, additional surface treatments are often used to extend service life.

6. Castability and Design Flexibility

Like other cast irons, ductile iron can be cast into complex shapes with high dimensional accuracy. This allows designers to create integrated parts that would be difficult or costly to manufacture from steel.

Strengths of Ductile Iron

The strengths of ductile iron are primarily attributed to its unique microstructure and alloying elements:

- Impact Resistance – Ductile iron’s structure provides excellent impact resistance, allowing it to absorb energy from sudden shocks without fracturing.

- Thermal Conductivity – It has good thermal conductivity, making it effective for heat transfer applications.

- Low Shrinkage – Ductile iron exhibits minimal shrinkage during the solidification process compared to other casting materials, reducing defects in the final product.

- Versatile Mechanical Properties – By adjusting the composition and production process, manufacturers can tailor the mechanical properties of ductile iron to fit specific application requirements.

Common Grades of Ductile Iron

Ductile iron grades are typically classified based on tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation. Examples include:

- Ferritic ductile iron: High ductility and good impact resistance

- Pearlitic ductile iron: Higher strength and wear resistance

- Ferritic-pearlitic ductile iron: Balanced properties for general use

- Austempered ductile iron (ADI): Very high strength-to-weight ratio and excellent fatigue resistance

Each grade is selected based on performance requirements and operating conditions.

Industrial Uses of Ductile Iron

Ductile iron’s unique properties make it ideal for a variety of industrial applications. Some of the most common uses include:

Automotive Components

Ductile iron is widely used in automotive parts such as crankshafts, engine blocks, and gears. Its strength-to-weight ratio makes it ideal for critical components that require both durability and reduced weight.

Pipelines and Fittings

Due to its corrosion resistance and strength, ductile iron is commonly used in water and sewage pipelines, as well as fittings and valves, ensuring reliable operation under high-pressure conditions.

Construction Materials

Ductile iron is used in various construction applications, including manhole covers, drainage grates, and support brackets. Its durability and load-bearing capacity are instrumental in infrastructure projects.

Conclusion

Ductile iron represents a significant advancement in materials science, offering an exceptional blend of strength, ductility, and resistance to wear and corrosion. Its unique properties make it suitable for a variety of applications, from automotive components to pipelines and construction materials.

As industries evolve, ductile iron remains crucial for innovation across sectors. Understanding its capabilities is essential for engineers and manufacturers, particularly at AlignMFG, where high-quality materials and advanced manufacturing techniques are prioritized to effectively meet client needs.

Casting vs Forging in Automotive Manufacturing: Which is Better?

In the world of automotive manufacturing, the choice of material processing methods significantly impacts the quality, performance, and cost of vehicle components. Two primary techniques, casting and forging, stand out for their unique advantages and applications. This article delves into casting and forging, comparing their processes, benefits, disadvantages, and the contexts in which each method is preferable.

What is Casting?

Casting is a manufacturing process where liquid material (usually metal) is poured into a mold to achieve a desired shape. Once the material cools and solidifies, it takes the form of the mold, allowing for intricate designs and complex geometries. The casting process includes several methods, such as sand casting, investment casting, and die casting, each with specific applications depending on the type of material and the required precision.

Key Characteristics of Casting:

- Complex Shapes: Casting can create more complex and intricate geometries that may be difficult or impossible to achieve with other manufacturing processes.

- Material Versatility: A wide range of materials can be used in casting, including aluminum, iron, and magnesium alloys.

- Scale Production: Efficient for large-scale production, especially when producing multiple parts that share identical geometries.

What is Forging?

Forging, on the other hand, involves shaping metal using localized compressive forces. This technique often employs hammers or presses to deform the metal into a desired shape. Like casting, forging also offers various methods, including open-die forging, closed-die forging, and precision forging.

Key Characteristics of Forging:

- Strength and Durability: Forged parts typically have enhanced mechanical properties due to the work-hardening of the material, offering better strength, fatigue resistance, and ductility.

- Less Waste: Forging usually results in less material waste compared to casting, as it involves deforming existing material rather than creating a new piece from molten metal.

- Lower Tolerances: Forged components often have tighter tolerances than cast parts, which can be crucial in applications where precision is key.

Comparison of Casting and Forging

When deciding whether to use casting or forging in automotive manufacturing, several factors come into play. Let’s compare the two processes based on various criteria:

1. Mechanical Properties

- Casting – The mechanical properties of cast parts can vary widely depending on the material used and the casting method employed. Generally, casting can lead to defects such as porosity and inclusions, impacting strength.

- Forging – Forged components typically exhibit superior mechanical properties such as greater strength and toughness. The process refines the internal grain structure of the metal, leading to improved performance in high-stress applications.

2. Geometric Complexity

- Casting – It excels in producing complex shapes and cavities that are difficult to achieve with forging. This makes it an excellent choice for components with intricate designs, such as engine blocks or cylinder heads.

- Forging – While forging may be limited in geometric complexity, it is more suitable for simpler, high-performance parts such as crankshafts, connecting rods, and gears.

3. Production Volume

- Casting – Best suited for large production runs due to its ability to easily replicate complex shapes. Once a mold is created, casting can be a cost-effective method for producing thousands of parts.

- Forging – Forging is often more economical for lower production volumes but can be costly for high volumes due to the machinery and tooling required for each component.

4. Material Waste

- Casting – Can produce considerable waste, especially if the design is not optimized. The excess material that does not fill the mold must be trimmed away.

- Forging – Generally incurs less waste as the bulk material is transformed into the final shape, retaining more of the original stock.

5. Cost Considerations

- Casting – The initial investment for molds can be high, but the low-cost per unit during mass production can offset this. Casting is typically the cheaper option for producing complex parts in bulk.

- Forging – The cost of manufacturing forged components can be higher due to the equipment requirements and lower production rates. However, the enhanced properties and performance of forged parts may justify the higher costs in applications where reliability is crucial.

Applications in the Automotive Industry

Both casting and forging play vital roles in automotive manufacturing, but their applications differ significantly:

Casting Applications:

- Engine blocks

- Cylinder heads

- Transmission cases

- Complex housings and brackets

Forging Applications:

- Crankshafts

- Connecting rods

- Gears

- Suspension components

Which Is Better?

There’s no single answer. The choice between casting and forging depends on application requirements, performance goals, cost constraints, and production volume:

| Criteria | Casting | Forging |

| Strength & Durability | Moderate | Excellent |

| Design Complexity | Excellent | Good |

| Cost Efficiency | Better for large runs | Higher tooling cost |

| Material Waste | Lower | Higher (but improving) |

| Production Speed | Faster | Slower |

In summary:

- Use forging for structural and high-stress components where strength matters most.

- Choose casting for complex shapes and high-volume parts where cost and flexibility are priorities.

Conclusion

In summary, both casting and forging have their advantages and disadvantages within automotive manufacturing. The choice between the two ultimately hinges on the specific needs of the application and the performance requirements of the components being made.

Additionally, the incorporation of automation in the casting process can enhance efficiency and consistency, making it a more appealing option for certain applications. By carefully evaluating these factors, manufacturers can select the most appropriate method to meet their production goals and ensure the performance of their vehicles.

What is Quenching? The Science of Rapid Steel Cooling

Quenching is a fundamental heat treatment process in metallurgy that involves the rapid cooling of steel after it has been heated to a high temperature. This sudden temperature change alters the steel’s internal structure, significantly improving properties such as hardness, strength, and wear resistance. According to ASM International, quenching is one of the most widely used thermal processes in modern manufacturing, especially for components that must withstand high mechanical stress.

In this article, we explore what quenching is, how it works at the atomic level, the science behind rapid steel cooling, and how manufacturers control the process to tailor material properties.

What Is Quenching?

Quenching is the process of rapidly cooling heated steel by immersing it in a liquid or gas medium such as water, oil, polymer solutions, or air. The primary objective of quenching is to lock in a specific microstructure that enhances hardness and strength.

In practical terms, quenching prevents steel from cooling slowly, which would otherwise result in softer structures like pearlite. Instead, rapid cooling forces the steel into a hardened state suitable for demanding applications such as gears, shafts, and cutting tools.

Why Quenching Is Used in Steel Processing

Quenching is used because steel’s mechanical properties are highly dependent on its cooling rate after heating. Slow cooling produces ductile but softer steel, while rapid cooling dramatically increases hardness.

Manufacturers rely on quenching to:

- Improve wear resistance

- Increase load-bearing capacity

- Extend component lifespan

- Prepare steel for secondary treatments such as tempering

Without quenching, many high-performance steel components would fail prematurely under stress or friction.

The Science Behind Rapid Steel Cooling

The science of quenching lies in phase transformation and atomic diffusion control. When steel is heated above its critical temperature (typically 723–900°C, depending on carbon content), its structure changes into a phase known as austenite.

At this stage, carbon atoms are evenly distributed within the iron lattice. Quenching rapidly removes heat, preventing carbon atoms from diffusing out. As a result, the lattice collapses into a distorted structure called martensite.

Austenite to Martensite Transformation

Martensite formation is the defining scientific outcome of quenching.

- Austenite is stable only at high temperatures.

- Rapid cooling traps carbon atoms in place.

- The trapped carbon causes lattice distortion.

- This distortion produces extreme hardness.

According to research published in MDPI Metals, martensitic steel can be up to four times harder than slowly cooled pearlitic steel.

How Quenching Works: Step-by-Step Process

The quenching process follows a precise sequence to achieve consistent results:

- Austenitizing: Steel is heated to a temperature where its structure becomes fully austenitic.

- Soaking: The steel is held at this temperature to ensure uniform heat distribution.

- Rapid Cooling (Quenching): The steel is immersed in a quenching medium to extract heat quickly.

- Microstructural Lock-In: Martensite forms as diffusion is suppressed.

- Post-Quench Evaluation: Hardness, distortion, and surface integrity are inspected.

Each step must be carefully controlled to avoid defects such as cracking or warping.

Quenching Media and Cooling Severity

The choice of quenching medium directly influences cooling speed, hardness, and risk of failure.

Common Quenching Media

| Quenching Medium | Cooling Rate | Advantages | Risks |

| Water | Very fast | High hardness | Cracking, distortion |

| Brine | Extremely fast | Maximum hardness | Severe thermal shock |

| Oil | Moderate | Reduced cracking | Lower hardness |

| Polymer solutions | Adjustable | Controlled cooling | Requires monitoring |

| Air / Gas | Slow | Minimal distortion | Limited hardness |

ASM Heat Treating Society notes that incorrect medium selection is one of the leading causes of quench-related failures in industrial environments.

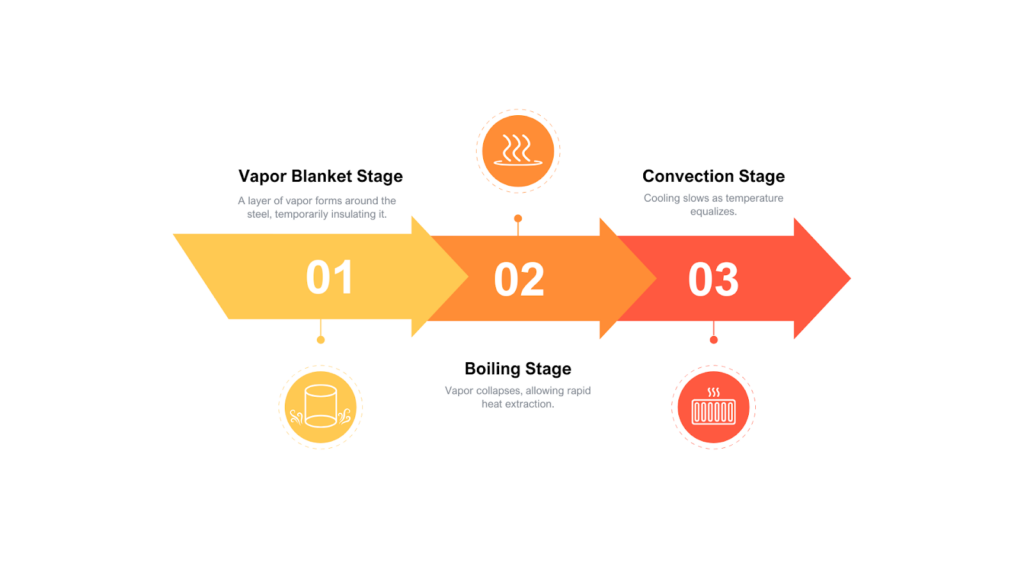

Heat Transfer Stages During Quenching

Quenching in liquid media occurs in three distinct heat transfer stages:

Understanding these stages allows engineers to fine-tune quenching systems for consistent results.

Mechanical Properties After Quenching

Quenched steel exhibits dramatic changes in mechanical performance.

Primary Property Improvements

- Increased hardness

- Improved wear resistance

- Higher tensile strength

However, these benefits come with trade-offs.

Residual Stress and Brittleness

While quenching increases hardness, it also introduces residual internal stresses. These stresses can lead to cracking if not properly managed. This is why quenching is rarely used alone and is typically followed by tempering.

Industrial Applications of Quenching

Quenching is widely used across industries that demand precision and durability.

Key Applications

- Automotive: Gears, crankshafts, suspension components

- Manufacturing: Cutting tools, dies, molds

- Construction: Structural fasteners, load-bearing elements

- Energy: Turbine shafts, drilling equipment

In automotive manufacturing alone, heat-treated and quenched steel components account for over 60% of critical drivetrain parts, as reported by industry analyses from ASM International.

Risks and Challenges of Quenching

While quenching delivers powerful benefits, it also introduces potential risks if poorly controlled.

Common Quenching Problems

- Cracking due to thermal shock

- Distortion from uneven cooling

- Surface oxidation

- Inconsistent hardness

Conclusion

Quenching is a vital heat treatment process that enables steel to achieve the hardness, strength, and durability required for demanding industrial applications. By rapidly cooling steel and controlling phase transformations, quenching allows manufacturers to precisely tailor material performance.

At Align MFG, quenching is treated as part of a fully integrated manufacturing strategy rather than a standalone step. Through careful control of materials, heat treatment parameters, and post-quench processes, Align MFG helps ensure steel components meet consistent performance standards and long-term reliability requirements.

Is Stainless Steel Magnetic? Understanding Ferritic vs Austenitic

Stainless steel magnetism depends largely on its internal crystal structure and alloy composition, not simply on the presence of iron. While many people assume all stainless steel is non-magnetic, the reality is more nuanced. Some stainless steel grades are magnetic, while others are not. This distinction is primarily driven by whether the material is ferritic or austenitic.

In this article, we’ll explain why stainless steel can be magnetic, compare ferritic and austenitic stainless steel, explore how processing affects magnetism, and clarify how magnetism influences real-world applications. By the end, you’ll have a clear, science-backed answer to one of the most common material-selection questions.

What Is Stainless Steel?

Stainless steel is an iron-based alloy containing a minimum of 10.5% chromium, which forms a thin, self-healing oxide layer that protects the metal from corrosion. Depending on additional alloying elements (such as nickel, molybdenum, or carbon) stainless steel can exhibit different mechanical, corrosion, and magnetic properties.

According to the British Stainless Steel Association (BSSA), stainless steels are categorized into five main families: austenitic, ferritic, martensitic, duplex, and precipitation-hardening steels. Among these, austenitic and ferritic stainless steels account for over 85% of global stainless steel usage, making them the most relevant when discussing magnetism.

Is Stainless Steel Magnetic? (Short Answer)

Yes, some stainless steels are magnetic, and others are not.

- Ferritic stainless steel is magnetic

- Austenitic stainless steel is generally non-magnetic

- Cold working can make some non-magnetic stainless steels slightly magnetic

The key factor behind this behavior is crystal structure, which determines how iron atoms and magnetic domains align inside the metal.

Why Magnetism Occurs in Metals

Magnetism in metals occurs when unpaired electrons align in a way that allows magnetic domains to form. Materials that support stable domain alignment are classified as ferromagnetic.

Key Factors Influencing Magnetism

- Atomic arrangement (crystal structure)

- Alloying elements (especially nickel)

- Phase stability at room temperature

- Mechanical processing such as cold rolling or bending

While pure iron is strongly magnetic, adding alloying elements can disrupt or suppress magnetic domain alignment, depending on how atoms are arranged.

Crystal Structure: The Real Reason Stainless Steel Is or Isn’t Magnetic

The magnetic behavior of stainless steel is governed by its crystallographic structure, not simply its chemical composition.

Common Stainless Steel Crystal Structures

| Crystal Structure | Name | Magnetic Behavior |

| BCC | Body-Centered Cubic | Magnetic |

| FCC | Face-Centered Cubic | Non-magnetic |

| BCT | Body-Centered Tetragonal | Magnetic |

Ferritic and martensitic steels use BCC or BCT structures, which allow magnetic domains to align. Austenitic steels use an FCC structure, which suppresses magnetism.

What Is Ferritic Stainless Steel?

Ferritic stainless steel is a class of stainless steel characterized by a body-centered cubic (BCC) crystal structure, which makes it naturally magnetic.

Key Characteristics of Ferritic Stainless Steel

- Magnetic in all conditions

- Contains 10.5–30% chromium

- Very low or no nickel content

- Moderate corrosion resistance

- Good resistance to stress corrosion cracking

Common ferritic grades include 430, 409, and 441.

Why Ferritic Stainless Steel Is Magnetic

Ferritic stainless steel remains magnetic because its BCC lattice allows electrons to align in stable magnetic domains. The absence of nickel prevents the stabilization of a non-magnetic phase, so the material behaves similarly to conventional steel when exposed to a magnetic field.

This makes ferritic stainless steel predictable in applications where magnetism must be accounted for, such as in automotive systems or industrial equipment.

What Is Austenitic Stainless Steel?

Austenitic stainless steel is the most widely used stainless steel family and is known for being generally non-magnetic in its annealed state.

Key Characteristics of Austenitic Stainless Steel

- Non-magnetic under normal conditions

- Face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure

- High nickel content (typically 8–12%)

- Excellent corrosion resistance

- High ductility and formability

Common austenitic grades include 304, 316, and 321, which dominate applications in food processing, medical devices, and chemical equipment.

Why Austenitic Stainless Steel Is Non-Magnetic

In austenitic stainless steel, nickel stabilizes the FCC structure at room temperature. This atomic arrangement disrupts magnetic domain alignment, resulting in extremely low magnetic permeability. As a result, magnets either do not stick at all or exhibit only negligible attraction.

This non-magnetic behavior is one of the reasons austenitic stainless steel is preferred in sensitive environments such as medical imaging rooms and electronic enclosures.

Ferritic vs Austenitic Stainless Steel: Key Differences

Ferritic and austenitic stainless steels differ primarily in crystal structure, alloy composition, and magnetic behavior, which directly affects how they perform in real-world applications.

| Property | Ferritic Stainless Steel | Austenitic Stainless Steel |

| Crystal structure | Body-centered cubic (BCC) | Face-centered cubic (FCC) |

| Magnetic behavior | Magnetic | Generally non-magnetic |

| Nickel content | Very low or none | Typically 8–12% |

| Corrosion resistance | Moderate | High |

| Formability | Limited | Excellent |

| Common grades | 430, 409 | 304, 316 |

Can Non-Magnetic Stainless Steel Become Magnetic?

Although austenitic stainless steel is classified as non-magnetic, it can develop weak magnetic properties after mechanical processing. This occurs because cold working introduces strain into the metal, causing a portion of the austenite to transform into martensite, which is magnetic.

This effect is most noticeable after operations such as:

- Cold rolling or forming

- Bending or stamping

- Heavy machining

Does Welding Affect Stainless Steel Magnetism?

Welding can introduce slight magnetic behavior in austenitic stainless steel, particularly near the weld zone. The intense heat can promote the formation of small amounts of ferrite, which improves weld strength but may attract a magnet.

In most cases, this magnetism is confined to the heat-affected zone and does not impact performance. It is considered a normal outcome of welding rather than a defect.

Magnetism in Duplex and Martensitic Stainless Steel

Duplex stainless steel contains both austenitic and ferritic phases, resulting in partial magnetism. Because ferrite is present in its microstructure, duplex stainless steel will respond to a magnet, although typically less strongly than fully ferritic grades. This balanced structure provides high strength and excellent corrosion resistance.

Martensitic stainless steel is fully magnetic due to its body-centered tetragonal structure. These steels can be heat treated for hardness and are commonly used in high-strength applications.

Typical examples include:

- Duplex grades for marine and oil applications

- Martensitic grades such as 410 and 420 for tools and wear-resistant components

Conclusion: Is Stainless Steel Magnetic?

Stainless steel may or may not be magnetic depending on its crystal structure and processing history. Ferritic stainless steel is magnetic due to its BCC structure, while austenitic stainless steel is generally non-magnetic because its FCC structure prevents magnetic domain alignment. Mechanical processing and welding can introduce limited magnetism, but they do not change the fundamental classification of the alloy.

At Align MFG, we help manufacturers select and fabricate stainless steel components based on real performance requirements. Understanding the relationship between microstructure and magnetism ensures better material choices, longer service life, and fewer surprises in production.

Anodizing vs Powder Coating: Which Finish Lasts Longer?

Anodizing and powder coating are two of the most widely used metal finishing processes for improving durability, corrosion resistance, and appearance. Anodizing is an electrochemical process that transforms the metal surface itself, while powder coating applies a protective polymer layer on top of the metal. According to manufacturing and architectural finishing data, surface treatments can extend the service life of aluminum components by 10–20+ years, depending on environment and usage.

This article compares anodizing and powder coating with a clear focus on which finish lasts longer. It covers how each process works, their durability mechanisms, performance in real-world environments, and the factors that directly influence lifespan.

What Is Anodizing?

Anodizing is an electrochemical finishing process that thickens and strengthens the natural oxide layer on aluminum, making it an integral part of the metal rather than a surface coating.

Unlike paints or coatings that sit on top of the material, anodizing converts the aluminum surface into a dense, corrosion-resistant oxide through controlled oxidation in an acid electrolyte bath.

How the Anodizing Process Works

The anodizing process involves:

- Submerging aluminum in an electrolytic solution (commonly sulfuric acid)

- Passing an electric current through the metal

- Growing a controlled aluminum oxide layer inward and outward from the surface

Because the oxide layer is part of the metal substrate, it cannot peel, flake, or blister, which is a critical factor in long-term durability.

Types of Anodizing and Their Durability

| Anodizing Type | Typical Use | Durability Level |

| Type I (Chromic) | Aerospace | Moderate |

| Type II (Sulfuric) | Architectural, consumer products | High |

| Type III (Hard Anodizing) | Industrial, marine, military | Very High |

Hard anodizing (Type III) can achieve surface hardness comparable to hardened steel, significantly improving wear resistance in harsh environments.

What Is Powder Coating?

Powder coating is a dry finishing process where finely ground polymer powder is electrostatically applied to metal surfaces and then cured under heat to form a smooth, protective layer.

Unlike anodizing, powder coating creates a separate external layer that bonds mechanically and chemically to the metal during curing.

How Powder Coating Works

The powder coating process includes:

- Surface cleaning and pretreatment

- Electrostatic spraying of powder particles

- Oven curing at temperatures typically between 160–200°C

The result is a thick, uniform finish that provides good corrosion resistance and excellent aesthetic flexibility.

Common Powder Coating Materials

Powder coatings vary widely in performance depending on formulation:

- Polyester powders – Good UV resistance for outdoor use

- Epoxy powders – Excellent adhesion but limited UV resistance

- Hybrid systems – Balance between durability and cost

Key Differences Between Anodizing and Powder Coating

The fundamental difference between anodizing and powder coating lies in how each finish protects the metal.

- Anodizing becomes part of the aluminum surface

- Powder coating acts as a protective shell over the surface

Bonding Mechanism Comparison

| Factor | Anodizing | Powder Coating |

| Bonding | Integrated with metal | Surface adhesion |

| Peeling Risk | None | Possible if damaged |

| Thickness | Thin but dense | Thick polymer layer |

| Repairability | Difficult | Easier to recoat |

Because anodizing is not a coating in the traditional sense, surface damage does not propagate peeling or widespread failure.

Durability and Wear Resistance

Durability refers to how well a finish withstands abrasion, impact, and daily wear over time.

Anodized aluminum offers superior abrasion resistance because the oxide layer is extremely hard and tightly bonded. Manufacturing studies consistently show anodized surfaces outperform powder-coated ones in scratch and wear testing.

Powder coating, while tough, is still a polymer-based finish. Sharp impacts or repeated friction can eventually chip or wear through the coating, exposing bare metal underneath.

Corrosion Resistance Over Time

Corrosion resistance plays a major role in determining which finish lasts longer, especially in outdoor, coastal, or humid environments.

Anodizing excels in corrosion resistance because:

- The oxide layer seals the aluminum surface

- Scratches do not spread corrosion beneath the finish

- Additional sealing treatments further enhance protection

Powder coating also provides good corrosion resistance, but its performance depends heavily on maintaining an intact coating layer. Once moisture penetrates through chips or cracks, corrosion can spread under the coating and shorten its lifespan.

UV and Environmental Resistance

Exposure to sunlight, humidity, and temperature extremes significantly affects the longevity of metal finishes.

- Anodizing: Naturally UV stable, meaning colors will not fade over time. Hard anodized layers can withstand high temperatures and harsh outdoor conditions without degradation.

- Powder Coating: UV stability depends on the powder formulation. Polyester-based powders are more UV resistant, whereas epoxy-based powders may fade or chalk in prolonged sun exposure. Extreme heat can also soften the coating if outside the recommended curing range.

Impact of Wear and Maintenance

Real-world performance is influenced by everyday wear and maintenance practices.

- Anodized surfaces are highly resistant to scratches and abrasion. Minor surface damage does not compromise corrosion protection. Repairing deep damage typically requires professional re-anodizing.

- Powder-coated surfaces can chip or scratch under heavy use. However, minor damage can be repaired with touch-up powder or spray coatings, although achieving the original smooth finish may be difficult.

Maintenance Tips for Longevity:

- Regular cleaning with non-abrasive detergents

- Prompt touch-up of any visible scratches or chips (for powder-coated surfaces)

- Avoid harsh chemical cleaners that can erode anodized or coated surfaces

Lifespan Comparison

Based on industrial studies and field observations:

| Finish | Estimated Lifespan | Key Factors |

| Anodizing | 15–20+ years | Hardness, oxide integration, environment, sealing quality |

| Powder Coating | 10–15 years | Coating thickness, UV-stable powder, surface prep, environmental exposure |

Conclusion

Both anodizing and powder coating enhance the durability and appearance of aluminum, but anodizing generally lasts longer due to its integration with the metal substrate, superior abrasion resistance, and natural UV stability. Powder coating provides excellent aesthetics and good corrosion resistance, but its lifespan is contingent on the integrity of the applied layer.

At Align MFG, we specialize in precision anodizing and powder coating services designed to meet the highest standards of durability and quality. By leveraging our expertise, clients can ensure that their architectural, industrial, or decorative projects achieve maximum longevity and maintain a premium finish.

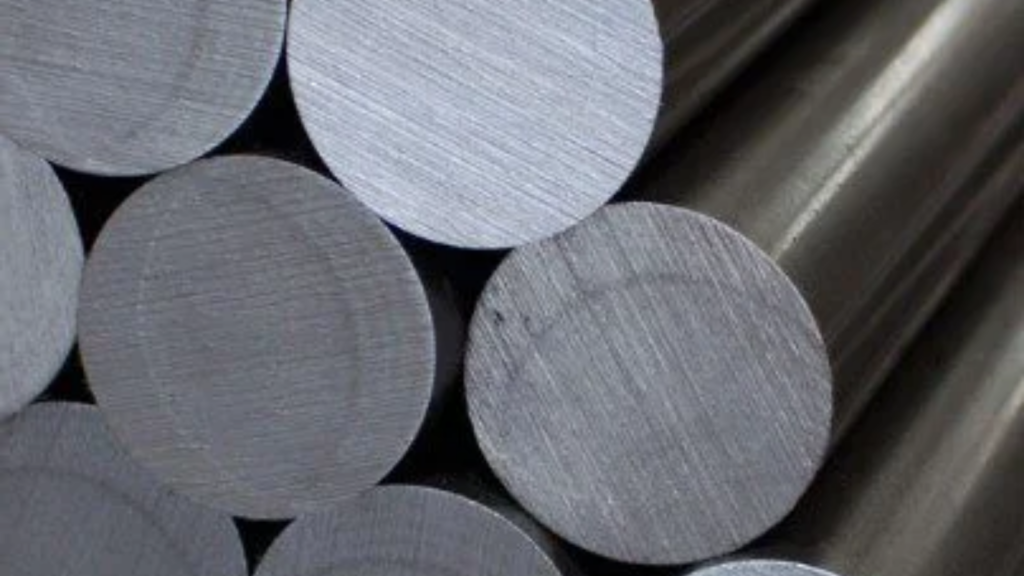

1045 Carbon Steel: Definition, Chemical Composition, Mechanical Properties, Applications

1045 carbon steel is a medium-carbon steel grade widely used in engineering and manufacturing due to its balanced combination of strength, toughness, and machinability. Containing approximately 0.43–0.50% carbon, it offers significantly higher strength than low-carbon steels while remaining cost-effective and versatile.

This guide explains what 1045 carbon steel is, its chemical and mechanical properties, how it performs under different heat treatments, and where it is commonly used. You’ll also learn about its advantages, limitations, and how it compares to other steel grades.

What Is 1045 Carbon Steel?

1045 carbon steel is a plain medium-carbon steel classified under the AISI/SAE system. It is primarily composed of iron and carbon, with small amounts of manganese and trace elements.

Unlike alloy steels, 1045 does not rely on chromium or nickel for performance. Instead, its strength comes from its carbon content and heat treatment capability, making it ideal for mechanical components subjected to moderate stress and wear.

Key defining characteristics include:

- Medium carbon content for higher strength

- Good response to heat treatment

- Moderate machinability and weldability

- Limited corrosion resistance without coatings

Chemical Composition of 1045 Carbon Steel

The chemical composition of 1045 carbon steel directly influences its hardness, strength, and heat-treating behavior.

Typical Chemical Composition Table

| Element | Percentage (%) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 0.43 – 0.50 | Increases strength and hardness |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.60 – 0.90 | Improves toughness and hardenability |

| Silicon (Si) | 0.15 – 0.40 | Strengthens ferrite structure |

| Phosphorus (P) | ≤ 0.04 | Residual impurity |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤ 0.05 | Improves machinability |

| Iron (Fe) | Balance | Base metal |

According to SteelPRO Group and MetalZenith, this composition allows 1045 steel to achieve higher mechanical strength than low-carbon grades like 1018, while remaining easier to process than high-carbon steels.

Physical Properties of 1045 Carbon Steel

The physical properties of 1045 carbon steel make it suitable for structural and rotating components.

Key Physical Properties

- Density: ~7.85 g/cm³

- Melting Point: 1450–1525°C

- Modulus of Elasticity: ~210 GPa

- Thermal Conductivity: Moderate

These properties allow 1045 steel to maintain dimensional stability under load and heat, which is critical for shafts, axles, and machine components.

Mechanical Properties of 1045 Carbon Steel

The mechanical performance of 1045 carbon steel varies depending on whether it is hot-rolled, normalized, or heat-treated.

Mechanical Properties (Normalized Condition)

| Property | Typical Value |

|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 570–700 MPa |

| Yield Strength | 310–450 MPa |

| Elongation | 12–20% |

| Hardness | 170–210 HB |

| Impact Energy | 25–35 J |

These values position 1045 steel as a middle-ground material—stronger than mild steel but not as brittle as high-carbon alternatives.

Microstructure of 1045 Carbon Steel

In its untreated state, 1045 carbon steel consists primarily of ferrite and pearlite.

- Ferrite: Provides ductility

- Pearlite: Provides strength and wear resistance

When quenched and tempered, the microstructure transforms partially into martensite, significantly increasing hardness and strength.

A 2023 materials science study published on ScienceDirect found that heat-treated 1045 steel exhibits significantly refined grain structures, improving fatigue and compressive strength.

Heat Treatment of 1045 Carbon Steel

Heat treatment plays a crucial role in tailoring the properties of 1045 carbon steel.

Common Heat Treatment Processes

Annealing

- Softens the steel

- Improves machinability

- Reduces internal stress

Normalizing

- Refines grain structure

- Improves strength and uniformity

Quenching and Tempering

- Increases hardness and tensile strength

- Achieves up to 800–1000 MPa tensile strength

Induction or Flame Hardening

- Hardens surface only

- Retains a tough, ductile core

While heat treatment improves performance, excessive hardening may reduce ductility if not controlled properly.

Machinability and Weldability

1045 carbon steel offers moderate machinability, especially in annealed or normalized conditions.

Machinability

- Rated ~55–65% compared to free-machining steel

- Suitable for turning, milling, and drilling

Weldability

- Fair but requires preheating and post-weld heat treatment

- Risk of cracking due to carbon content

While easier to machine than high-carbon steels, 1045 requires more care than low-carbon steels during welding.

Corrosion Resistance of 1045 Carbon Steel

1045 carbon steel has limited corrosion resistance because it lacks alloying elements such as chromium or nickel that protect against oxidation.

Why 1045 Steel Rusts Easily

- High iron content reacts with moisture and oxygen

- No passive oxide layer forms naturally

- Accelerated corrosion in humid or marine environments

According to Rapid-Protos and Langhe Industry, untreated 1045 steel will oxidize quickly when exposed to water or chemicals, making surface protection essential.

Common Corrosion Protection Methods

- Painting or powder coating

- Oil or grease coatings

- Electroplating (nickel or chrome)

- Hot-dip galvanizing

While these treatments increase service life, they also add cost—an important tradeoff when selecting materials.

Applications of 1045 Carbon Steel

1045 carbon steel is widely used across industries that require strength, durability, and cost efficiency.

Industrial and Mechanical Applications

- Transmission shafts

- Axles and spindles

- Gears and sprockets

- Connecting rods

These components benefit from 1045’s ability to withstand repeated stress without excessive deformation.

Automotive Applications

- Crankshafts

- Steering components

- Suspension parts

Automotive manufacturers favor 1045 steel because it can be heat-treated for fatigue resistance while remaining affordable for mass production.

Agricultural and Heavy Equipment

- Tractor pins and shafts

- Hydraulic components

- Wear-resistant machine parts

Tooling and Fabrication

- Bolts and studs

- Rollers and pins

- Medium-duty tooling components

FindTop reports that 1045 steel is often selected when 1018 steel lacks strength but alloy steels would be unnecessarily expensive.

Advantages of 1045 Carbon Steel

The popularity of 1045 carbon steel stems from its balanced performance profile.

Key Benefits

- High strength-to-cost ratio

- Good response to heat treatment

- Versatile machining capability

- Wide availability worldwide

Compared to alloy steels, 1045 offers lower material and processing costs, making it ideal for general engineering use.

Limitations and Drawbacks

Despite its advantages, 1045 carbon steel has notable limitations.

Primary Limitations

- Poor corrosion resistance

- Moderate weldability

- Lower wear resistance than alloy steels

- Not ideal for extreme temperatures

While alloy steels like 4140 outperform 1045 in demanding environments, they come with higher costs and more complex processing requirements.

1045 Carbon Steel vs Other Steel Grades

Understanding how 1045 compares to other steels helps engineers make informed material decisions.

Comparison Table

| Steel Grade | Carbon Content | Strength | Weldability | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1018 | ~0.18% | Low | Excellent | Low |

| 1045 | ~0.45% | Medium-High | Moderate | Medium |

| 4140 | ~0.40% + alloy | High | Moderate | High |

Key takeaway:

- Choose 1018 for fabrication and welding

- Choose 1045 for strength-driven components

- Choose 4140 for high-stress, fatigue-critical parts

Common Buyer FAQs

Is 1045 carbon steel good for machining?

Yes, especially in annealed condition. However, it is harder to machine than low-carbon steels.

Can 1045 steel be hardened?

Yes. Quenching and tempering significantly increase hardness and strength.

Is 1045 steel suitable for outdoor use?

Only with protective coatings, as it corrodes easily.

Is 1045 steel stronger than mild steel?

Yes. It offers significantly higher tensile and yield strength than mild steels like 1018.

Conclusion

1045 carbon steel is a versatile, medium-carbon steel that offers an excellent balance between strength, toughness, and cost. Its ability to respond to heat treatment makes it suitable for a wide range of industrial, automotive, and mechanical applications.

While it lacks corrosion resistance and requires care during welding, these limitations are often offset by surface treatments and proper processing. For engineers seeking a reliable, cost-effective steel for load-bearing components, 1045 remains one of the most practical choices available.

1045 carbon steel remains one of the most practical and widely used medium-carbon steels due to its strong balance of mechanical performance, heat-treat responsiveness, and cost efficiency. Its versatility makes it a dependable choice for shafts, axles, gears, and other load-bearing components where higher strength than mild steel is required without the added expense of alloy grades. When paired with proper heat treatment and surface protection, 1045 steel delivers consistent performance across demanding industrial environments.

At Align Manufacturing, we work closely with clients to select and process materials like 1045 carbon steel to meet real-world application requirements—especially for precision components such as oil and gas gears, where durability, dimensional accuracy, and reliability are critical. By combining material expertise with controlled manufacturing processes, we help ensure that every component performs as intended throughout its service life. If you’re evaluating carbon steel options for mechanical or energy-sector applications, our engineering team is ready to support your next production challenge.

Understanding Austenitic Stainless Steel: Definition, Grades, Properties, Applications

Austenitic stainless steel is a widely used class of stainless steel known for its exceptional corrosion resistance, strength, and versatility across industries. It is characterized by a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure stabilized primarily by chromium and nickel, making it suitable for demanding environments such as food processing, marine, medical, and chemical applications. According to materials industry data, austenitic stainless steels account for over 50% of global stainless steel production, with grades like 304 and 316 dominating commercial use.

This article explores what austenitic stainless steel is, its core properties, major grades, and real-world applications, followed by material selection considerations, limitations, and industry standards.

What Is Austenitic Stainless Steel?

Austenitic stainless steel is a category of stainless steel alloys defined by their austenitic microstructure, which provides high ductility, toughness, and corrosion resistance. This structure is achieved through alloying elements such as chromium and nickel, which stabilize the FCC lattice at room temperature.

Unlike ferritic or martensitic stainless steels, austenitic grades are generally non-magnetic in their annealed state and cannot be hardened through heat treatment, relying instead on cold working for strength enhancement.

Chemical Composition of Austenitic Stainless Steel

The performance of austenitic stainless steel is primarily determined by its alloying elements.

Key Alloying Elements

- Chromium (16–26%)

Forms a passive oxide layer that protects against corrosion. - Nickel (6–22%)

Stabilizes the austenitic structure and improves toughness. - Molybdenum (0–3%)

Enhances resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion, especially in chloride environments. - Carbon (≤0.08% or ≤0.03% for low-carbon grades)

Lower carbon improves weldability and reduces intergranular corrosion.

Entity–Attribute–Outcome Example:

(Chromium → forms → corrosion-resistant passive film)

Key Properties of Austenitic Stainless Steel

1. Corrosion Resistance

Austenitic stainless steel offers excellent resistance to atmospheric, chemical, and aqueous corrosion. The chromium-rich passive layer self-heals when damaged, making the material highly durable.

- Grade 316 performs especially well in marine and chemical environments due to molybdenum content.

- According to materials engineering studies, molybdenum increases pitting resistance in chloride-rich conditions by up to 3× compared to grade 304.

2. Mechanical Strength and Ductility

Austenitic stainless steels are known for their high ductility and toughness, even at extremely low temperatures.

- Retains strength at cryogenic temperatures (below –196°C)

- Can be strengthened through cold working

- Exhibits excellent impact resistance

While martensitic steels can be harder, they lack the ductility and corrosion resistance of austenitic grades—highlighting an important engineering trade-off.

3. Weldability and Fabrication

Austenitic stainless steels are among the most weldable stainless steel families.

- Low-carbon variants such as 304L and 316L reduce the risk of weld sensitization.

- Stabilized grades like 321 and 347 prevent carbide precipitation during high-temperature welding.

This makes them ideal for pressure vessels, piping systems, and fabricated structures.

4. Temperature Performance

Austenitic stainless steels maintain structural integrity across a wide temperature range.

| Temperature Range | Performance |

|---|---|

| Cryogenic | Excellent toughness |

| Ambient | Optimal corrosion resistance |

| High-temperature (up to 870°C) | Oxidation resistance |

Grades such as 310 and 310S are specifically designed for high-temperature service in furnaces and heat exchangers.

Major Austenitic Stainless Steel Grades

Austenitic stainless steels are primarily grouped within the 300 series, each grade optimized for specific performance needs.

Grade 304 / 304L

Grade 304 is the most widely used austenitic stainless steel, often referred to as 18-8 stainless steel due to its composition.

- Composition: ~18% chromium, ~8–10% nickel

- Key Benefits: General corrosion resistance, excellent formability

- Common Uses:

- Food processing equipment

- Kitchenware

- Storage tanks

- Architectural panels

304L offers lower carbon content for improved weldability.

Grade 316 / 316L

Grade 316 includes molybdenum, making it more resistant to aggressive environments.

- Key Advantage: Superior resistance to chlorides and chemicals

- Industries:

- Marine

- Chemical processing

- Pharmaceutical manufacturing

According to corrosion engineering research, 316 stainless steel can last 2–3 times longer than 304 in marine environments.

Austenitic stainless steel continues to be a cornerstone material across modern manufacturing due to its outstanding corrosion resistance, mechanical reliability, and adaptability across industries. From food processing and medical equipment to marine and chemical environments, understanding grade differences such as 304, 316, or high-alloy variants allows engineers and buyers to make informed material decisions that balance performance, durability, and cost. Selecting the right grade is not just a technical choice—it directly impacts product lifespan, safety, and long-term operational efficiency.

Grade 310 / 310S

Grade 310 is designed for high-temperature performance.

- Higher chromium and nickel content

- Exceptional oxidation resistance

- Used in furnace components, heat exchangers, and thermal processing equipment

Grade 321 and 347

These are stabilized austenitic stainless steels.

- 321: Stabilized with titanium

- 347: Stabilized with niobium

They are ideal for applications involving repeated heating cycles, such as aerospace exhaust systems and high-temperature piping.

Grade 904L

904L is a high-alloy austenitic stainless steel with copper addition.

- Outstanding resistance to sulfuric acid

- Used in chemical plants and specialty industrial applications

- Higher cost due to elevated nickel and alloy content

Applications of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Food and Beverage Industry

Austenitic stainless steel is the preferred material for hygienic environments.

- Non-reactive and easy to clean

- Complies with food safety regulations

- Grade 304 dominates food processing equipment

Chemical and Process Industries

Due to corrosion resistance, austenitic stainless steels are used in:

- Chemical storage tanks

- Heat exchangers

- Piping systems

Grade 316L is commonly specified for aggressive chemical exposure.

Marine and Offshore Applications

Marine environments expose materials to saltwater and humidity.

- Grade 316 resists pitting corrosion

- Used in boat fittings, railings, and offshore platforms

Medical and Pharmaceutical Equipment

Austenitic stainless steels are ideal for medical use because they:

- Resist sterilization chemicals

- Maintain structural integrity

- Meet biocompatibility standards

Architectural and Structural Uses

Used in:

- Facades

- Handrails

- Decorative panels

Their aesthetic finish and durability make them popular in modern architecture.

Material Selection Considerations

When selecting an austenitic stainless steel grade, engineers consider:

- Exposure environment (chlorides, chemicals)

- Operating temperature

- Weldability requirements

- Budget constraints

While higher alloy content improves performance, it also increases cost—making grade selection a balance between performance and economics.

Limitations of Austenitic Stainless Steel

Despite their advantages, austenitic stainless steels have limitations:

- Susceptible to stress corrosion cracking in specific environments

- Lower hardness compared to martensitic steels

- Higher cost due to nickel content

Understanding these trade-offs is critical for proper material selection.

Standards and Classification Systems

Austenitic stainless steels are classified using international standards:

- AISI / SAE: Common U.S. designation

- UNS: Unified numbering system (e.g., S30400)

- ASTM / EN / ISO: Performance and testing standards

These systems ensure material consistency across global supply chains.

Conclusion

Austenitic stainless steel is the most versatile and widely used stainless steel family due to its corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, and fabrication flexibility. Grades such as 304 and 316 dominate applications across food, chemical, medical, marine, and architectural industries.

Understanding the differences between grades—and matching them to operating conditions—ensures long-term performance and cost efficiency. For engineers, designers, and buyers, austenitic stainless steel remains a cornerstone material for modern industry.

At Align Manufacturing, we support manufacturers in translating material knowledge into real-world production outcomes. Whether your project involves stainless steel components, complex industrial parts, or complementary processes such as sand casting Thailand, our team focuses on precision, material suitability, and manufacturing alignment from design to delivery. By combining material expertise with regional manufacturing capabilities, Align Mfg helps ensure your components are built to perform in demanding environments—today and over the long term.

Lost Wax Casting Process: Definition, Steps, Diagram Explanation, Applications

The lost wax casting process—also known as investment casting—is a manufacturing technique used to produce highly detailed metal components by creating a disposable wax model that is replaced with molten metal. This method has been used for over 6,000 years, from ancient bronze sculptures to modern aerospace and medical components, due to its ability to deliver exceptional precision and surface finish.

Today, lost wax casting is valued across industries for producing complex geometries, tight tolerances, and near-net-shape parts with minimal machining. In this guide, we’ll walk through the step-by-step lost wax casting process, explain each stage with diagram references, explore its advantages and applications, and address limitations and best practices.

What Is the Lost Wax Casting Process?

The lost wax casting process is a metal casting method in which a wax pattern is coated with a ceramic shell, the wax is melted out, and molten metal is poured into the resulting cavity to form a final part.

This process is especially effective for:

- Intricate shapes

- Thin walls

- Fine surface details

- Hard-to-machine metals

According to Wikipedia and multiple industrial foundries, investment casting can achieve dimensional tolerances as tight as ±0.1 mm, significantly reducing secondary machining requirements.

Why Lost Wax Casting Is Still Widely Used

The continued relevance of lost wax casting is driven by its unique combination of precision, flexibility, and material compatibility.

Key reasons industries rely on this process include:

- Ability to cast complex internal geometries

- Superior surface finish compared to sand casting

- Compatibility with ferrous and non-ferrous alloys

- Scalability from one-off art pieces to mass production

While alternative methods like die casting offer speed, they often lack the geometric freedom that lost wax casting provides.

Lost Wax Casting Process: Step-by-Step Explanation

Below is a structured breakdown of each stage in the lost wax casting process. Each step corresponds directly to common process diagrams used in manufacturing guides.

Step 1: Creating the Wax Pattern

The process begins with the creation of a wax pattern, which serves as the exact replica of the final metal part.

How it works:

- Wax is injected into a metal die or created using 3D printing

- The wax model includes all surface details, text, and geometry

- Dimensional accuracy at this stage determines final part quality

Why this step matters:

Any imperfection in the wax pattern will appear in the final metal casting. This is why high-precision wax injection and inspection are critical.

Modern foundries increasingly use 3D-printed wax or polymer patterns to improve repeatability and reduce tooling time.

Step 2: Assembling the Wax Tree (Gating System)

Once individual wax patterns are complete, they are attached to a central wax sprue to form a wax tree.

Purpose of the wax tree:

- Allows molten metal to flow evenly

- Enables multiple parts to be cast simultaneously

- Controls shrinkage and solidification behavior

Diagram reference:

In standard diagrams, this step shows multiple wax parts branching off a central channel, resembling a tree structure.

While this increases production efficiency, poor gating design can lead to defects such as porosity or incomplete fills.

Step 3: Ceramic Shell Coating

The wax tree is repeatedly dipped into a ceramic slurry and coated with fine sand or refractory material.

This step involves:

- Multiple dipping and drying cycles

- Gradual shell thickness buildup

- Use of silica or zircon-based materials

According to industrial casting suppliers, 6–9 layers are typically required to form a shell strong enough to withstand molten metal temperatures exceeding 1,400°C.

Why this step matters:

The ceramic shell becomes the final mold. Its strength, permeability, and thermal resistance directly affect surface finish and casting accuracy.

Step 4: Drying and Hardening the Ceramic Shell

After coating, the ceramic shell must fully air-dry and harden before further processing.

Key objectives of this stage:

- Remove moisture to prevent cracking

- Strengthen the shell structure

- Prepare for high-temperature exposure

This stage is often overlooked, but inadequate drying is a common cause of shell failure during metal pouring.

Step 5: Dewaxing – Removing the Wax

Once hardened, the ceramic shell undergoes dewaxing, where the wax pattern is melted and drained out.

Common dewaxing methods include:

- Steam autoclave

- Flash fire furnace

- Controlled kiln heating

The melted wax is often recovered and reused, improving sustainability.

Diagram reference:

Diagrams show molten wax flowing out of the inverted ceramic shell, leaving a hollow cavity—hence the term “lost wax.”

Step 6: Shell Firing and Mold Preparation

After dewaxing, the empty ceramic mold is fired at high temperatures to:

- Burn off wax residue

- Increase shell strength

- Preheat the mold for metal pouring

Preheating helps molten metal flow smoothly into fine details and prevents thermal shock.

Step 7: Pouring the Molten Metal

After the ceramic shell is fired and preheated, molten metal is poured into the hollow cavity left by the melted wax.

Common metals used include:

- Aluminum and aluminum alloys

- Bronze and brass

- Carbon steel and stainless steel

- Nickel-based superalloys

According to industrial casting references, metals are typically poured at temperatures ranging from 650°C (aluminum) to 1,600°C (steel and superalloys).

Why this step matters:

The temperature of both the metal and the ceramic mold determines how well fine details are filled. Poor temperature control can result in misruns, cold shuts, or surface defects.

Diagram reference:

This stage is often illustrated with molten metal flowing into the ceramic mold through the sprue system.

Step 8: Cooling and Solidification

Once poured, the molten metal is allowed to cool and solidify inside the ceramic shell.

Key factors during cooling:

- Cooling rate affects grain structure and strength

- Controlled cooling reduces internal stress

- Thicker sections cool slower than thin walls

From a metallurgical perspective, slower cooling generally improves ductility, while faster cooling can increase hardness.

Step 9: Shell Removal (Knockout Process)

After solidification, the ceramic shell is mechanically or chemically removed to reveal the raw metal casting.

Shell removal methods include:

- Vibration and hammering

- High-pressure water jets

- Chemical dissolution (for delicate parts)

Diagram reference:

Most diagrams show the ceramic shell being broken away, exposing the metal tree beneath.

This stage transitions the process from molding to finishing.

Step 10: Cutting, Finishing, and Inspection

The individual cast parts are cut from the metal tree and undergo finishing operations.

Common finishing steps include:

- Grinding and sanding

- Polishing or surface treatment

- Heat treatment for mechanical properties

- Dimensional and non-destructive testing

According to manufacturing quality standards, investment casting often achieves a surface roughness of Ra 1.6–3.2 μm, significantly smoother than sand casting.

Lost Wax Casting Diagram: Process Recap

A complete lost wax casting diagram typically includes:

- Wax pattern creation

- Wax tree assembly

- Ceramic shell coating

- Drying and hardening

- Dewaxing

- Shell firing

- Molten metal pouring

- Cooling and solidification

- Shell removal

- Finishing and inspection

Using labeled diagrams alongside each step improves understanding, especially for educational and industrial audiences.

Applications of Lost Wax Casting

Lost wax casting is widely used across multiple industries due to its precision and versatility.

Jewelry and Art

- Fine details and textures

- Custom and small-batch production

- Sculptures and ornamental pieces

Aerospace and Automotive

- Turbine blades

- Engine components

- Structural parts with tight tolerances

Medical and Industrial Equipment

- Surgical instruments

- Valve components

- Pumps and fittings

According to industry suppliers, investment casting reduces machining costs by up to 40% compared to traditional fabrication methods.

Advantages of the Lost Wax Casting Process

The benefits of lost wax casting include high accuracy, flexibility, and superior surface quality.

Key advantages:

- Excellent dimensional precision

- Ability to cast complex geometries

- Minimal material waste

- Wide range of compatible metals

These advantages make the process ideal for parts that are difficult or expensive to machine.

Limitations and Challenges

While highly effective, lost wax casting is not without drawbacks.

Potential limitations include:

- Higher upfront tooling costs

- Longer production lead times

- Not ideal for very large components

Counterpoint:

While die casting offers faster cycle times, it lacks the design freedom and material range of investment casting.

Common Defects and How to Avoid Them

Some defects can occur if the process is not properly controlled.

| Defect | Cause | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Porosity | Trapped gas | Proper venting |

| Cracks | Rapid cooling | Controlled cooling |

| Incomplete fill | Low pour temperature | Preheated molds |

| Surface flaws | Poor shell quality | Consistent slurry coating |

Regular inspection and process optimization significantly reduce defect rates.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is lost wax casting expensive?

It can be costlier upfront, but lower machining and material waste often offset initial costs.

Can lost wax casting be used for mass production?

Yes. While ideal for small batches, automated wax injection allows for scalable production.

How accurate is investment casting?

Tolerances of ±0.1 mm are common, depending on size and alloy.

Conclusion

The lost wax casting process remains one of the most reliable methods for producing complex, high-precision metal components, combining centuries-old craftsmanship with modern manufacturing control. From wax pattern creation to final inspection, each step plays a critical role in achieving consistent quality, tight tolerances, and superior surface finishes. For industries that demand reliability—such as aerospace, medical devices, and energy—this method offers a proven balance between design freedom and production efficiency, especially when supported by strong process control investment castings practices.

At Align Manufacturing, we apply this deep process understanding across a broad range of casting solutions, helping clients select the right method based on performance, cost, and application requirements. Whether you are comparing investment casting with alternatives like sand casting Thailand suppliers or evaluating regional production strategies, our team ensures every project is engineered for precision, durability, and long-term value. By combining technical expertise with regional manufacturing insight, Align Manufacturing delivers casting solutions that align seamlessly with your production goals.

Why Vietnam Is a Hidden Gem for Gravity Casting

When companies look beyond traditional manufacturing hubs, they increasingly discover that Vietnam gravity casting offers a uniquely advantageous mix of cost, capability, and flexibility. As global demand grows for precision-cast metal parts, Vietnam is quietly emerging as a go-to destination. In this article, we explore why gravity casting in Vietnam deserves more attention than it currently gets.

Gravity casting (also called permanent mold casting) is a process where molten metal is poured into a reusable metal mold without external pressure. It sits between sand casting (lower tooling cost, rougher finish) and high-pressure die casting (higher tooling cost, highest throughput).

Core advantages include:

- Better mechanical properties than sand casting due to faster cooling in metal molds

- Improved surface finish and dimensional repeatability vs. sand casting

- Longer mold life and lower porosity than sand casting

- Lower capital/tooling cost and less porosity risk than high-pressure die casting for medium volumes

Why Vietnam for Gravity Casting?

1. Competitive Cost Structure Without Sacrificing Quality

Vietnam offers significantly lower labor and overhead costs while still maintaining dependable casting quality. Many foundries operate with international standards in mind, giving buyers an attractive combination of cost savings and consistent performance across a wide range of gravity-cast metal parts.

2. Skilled Workforce and Growing Industrial Expertise

The country’s casting sector has rapidly modernized, with foundries investing in better equipment, training, and process control. As a result, Vietnam now supports more complex and higher-tolerance gravity castings for industries like automotive, machinery, and heavy equipment.

3. Material Flexibility & Suitability for Medium-to-Large Castings

Vietnamese foundries handle a wide variety of alloys and specialize in gravity casting parts that benefit from strength, durability, and medium-to-large dimensions. This makes Vietnam well-suited for components such as housings, fittings, and industrial equipment parts that don’t require ultra-thin walls.

4. Strategic Export Location and Supply-Chain Accessibility

With strong logistics links and an export-oriented manufacturing base, Vietnam offers shorter lead times and simpler global shipping compared with more distant industrial hubs. Many gravity-casting suppliers already work with international buyers, making onboarding smoother and more predictable.

5. Modernizing Infrastructure and Increasing Capabilities

Vietnam’s foundry industry has shifted from small artisanal operations to facilities equipped with modern melting systems, improved molding technology, and integrated machining. This ongoing upgrade boosts reliability and expands the types of projects that can be supported locally.

Qualitative regional comparison (indicative)

| Factor | Vietnam | China | India | Thailand |

| Tooling Cost | Low–Medium | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Casting + Machining Cost | Low–Medium | Medium | Low–Medium | Medium |

| Quality Systems Maturity | High (growing) | High | Medium–High | High |

| Export Logistics | Strong | Strong | Medium | Strong |

| FTA Coverage | Broad | Broad | Broad | Broad |

Conclusion

For manufacturers seeking dependable, cost-efficient casting solutions, gravity casting Vietnam stands out as a powerful and often overlooked option. With improving capabilities, competitive pricing, and a globally connected industrial base, Vietnam is well-positioned to support high-quality gravity-cast components while strengthening supply-chain resilience. As sourcing strategies evolve, Vietnam’s gravity-casting sector offers the flexibility and value that modern manufacturing demands.